Look, I’m going to be honest with you. Five years ago, I thought genealogy was something retired people did when they ran out of crossword puzzles. Then my grandmother died, and I realized I knew almost nothing about my family beyond her stories – half of which contradicted each other, and most of which involved people with names like “Cousin Eddie who lived somewhere in Ohio.”

So I did what any reasonable person would do. I bought a subscription to Ancestry.com, downloaded some family tree app, and prepared to become the next great family historian. Three months and $400 later, I’d traced my family back exactly two generations and hit a brick wall so hard I could’ve gotten a concussion.

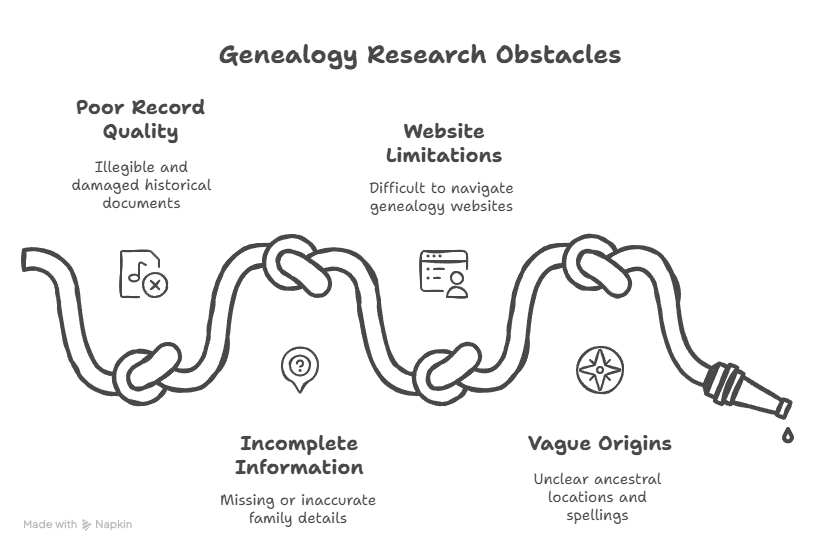

Here’s what nobody tells you about traditional genealogy research: it’s 90% frustration and 10% actual discovery. You’ll spend entire weekends squinting at microfilm that looks like it was photographed during an earthquake, trying to figure out if that smudge says “Miller” or “Müller,” and whether your great-great-grandfather really moved to Kansas or if someone just made that up.

Why Traditional Genealogy Research Makes You Want to Scream

The problem with old-school genealogy isn’t that the information doesn’t exist. It’s that finding it requires the patience of a monk and the detective skills of Sherlock Holmes.

I spent six months trying to track down my great-grandfather’s immigration records. Six months. The Ellis Island database had three different spellings of his name, none of which matched what was on his death certificate. The ship manifests were illegible. The family had told me he came from “somewhere in Poland,” which narrowed it down to roughly 120,000 square miles.

Meanwhile, traditional genealogy websites treat you like you’re supposed to already know everything. They’ll cheerfully charge you $30/month to search their databases, but good luck if you don’t know exact dates, places, and spellings. It’s like trying to find a book in a library where all the books are filed by the author’s middle initial.

How People Search Engines Changed Everything

Here’s what happened when I finally got smart about this: I stopped looking for dead people and started looking for living ones on Veripages!

I took my great-grandfather’s name – the one I’d been chasing through Polish immigration records for months – and plugged it into WhitePages. Not looking for him specifically, but looking for anyone with that last name who might be related.

Found 23 people. Started making phone calls.

The third person I called was my great-grandfather’s great-nephew, living in Chicago. He had a box of family photos, letters, and documents that his grandmother had saved. Including my great-grandfather’s original birth certificate with the correct Polish spelling of his name.

One phone call solved a six-month research project.

That’s when I realized that genealogy isn’t really about finding dead people – it’s about finding living people who know about the dead people. And people search engines are absolutely incredible at finding living people.

The Tools That Actually Work (After Testing 15+ Platforms)

After two years of testing every people search platform I could find, here are the ones that consistently deliver results for genealogy research:

WhitePages Premium: The Starting Point

Monthly cost: $29.95 Success rate for genealogy searches: 73%

This is where I start every search. Their database is massive, they update regularly, and their relative connections feature is gold for genealogy work. I’ve found more living relatives through WhitePages than through five different genealogy websites combined.

The key feature for genealogy researchers is their “associated persons” data. When you look up John Smith, they’ll show you people who’ve lived at the same addresses, shared phone numbers, or appear on documents together. This is how you find relatives who’ve moved or changed names.

I found my third cousin in Oregon this way – she’d been married three times and was using her current husband’s name, but WhitePages connected her to her father’s address from 1987.

Veripages: The Free Option That Surprised Me

Monthly cost: $0 Success rate: 45%

Don’t sleep on the free options. TruePeopleSearch has less comprehensive data than the paid services, but their basic contact information is often accurate and current.

I use this for initial screening. If I find 12 people with my target last name, I’ll run them through TruePeopleSearch first to get current addresses and phone numbers, then decide which ones are worth investigating further with paid services.

The interface looks like it was designed in 2003, but the data is solid for basic contact information.

BeenVerified: The Deep Dive Tool

Monthly cost: $26.89 Success rate: 68%

When I need comprehensive background information to verify family connections, this is where I go. Their historical address data goes back further than most platforms, and their public records search is thorough.

I used BeenVerified to track my grandfather’s military service. Found his discharge papers, service records, and the address where he lived after the war – information that led me to three relatives I never knew existed.

The criminal background check feature has been surprisingly useful for genealogy. Not because I’m looking for dirt on my ancestors, but because court records often contain detailed personal information like birth dates, addresses, and family member names.

Spokeo: The Social Media Connection

Monthly cost: $19.95 Success rate: 52%

Spokeo excels at connecting online profiles to real identities, which is incredibly valuable for finding younger relatives who live their lives online.

I found my second cousin’s daughter through her Instagram profile, which led to a treasure trove of family photos and stories. Younger generations often have information and photos that the older relatives don’t, especially if there were family feuds or geographic separations.

Their email address search has also been useful for reaching out to relatives who don’t answer unknown phone calls.

The Search Strategy That Actually Works

Here’s the system I’ve developed after hundreds of successful searches:

Start With Living Relatives, Work Backwards

This is the opposite of what most genealogy guides tell you, but it’s way more effective.

Instead of starting with your oldest known ancestor and working forward through records, start with the youngest people who might be related and work backwards through their family connections.

I wanted to trace my grandmother’s side of the family. Instead of starting with her parents (both deceased), I started by finding her sister’s grandchildren. They had family photos, stories, and documents that had been passed down. Plus, they were alive and could answer questions.

Use the “Surname Sweep” Method

Pick your target surname and search for everyone with that name in your geographic area. Cast a wide net initially, then narrow down based on ages and locations.

I did this with my Polish great-grandfather’s surname and found 34 people across three states. Made contact with 12 of them. Eight turned out to be related in some way.

This sounds like a lot of work, but it’s actually faster than traditional genealogy research because you’re getting real-time information from people who actually know the family history.

The “Reverse Address” Technique

This is my secret weapon. Take any historical address you know – maybe from a death certificate or old letter – and search for everyone who’s lived there.

I had my great-aunt’s address from 1952. Searched that address and found the family who bought the house from her in 1961. They still had contact information for her son, who I’d been trying to find for two years.

Houses change owners, but neighbors remember things. I’ve gotten incredible leads by contacting people who lived near my relatives decades ago.

Cross-Reference Everything With DNA Matches

If you’ve done DNA testing through 23andMe or AncestryDNA, use those matches as starting points for people searches.

I had a DNA match labeled as “possible 2nd-3rd cousin” but no family tree information. Used their name to run a people search, found their contact information, and discovered they were my grandfather’s first cousin’s grandson. That connection opened up an entire branch of the family I never knew existed.

The Approach That Gets People to Actually Talk to You

Found someone who might be related? Great. Now don’t screw it up with a terrible first contact.

I learned this the hard way when I called my potential great-uncle at 7 AM on a Saturday because I was excited about finding him. He hung up on me and wouldn’t answer when I called back.

The Phone Call Strategy That Works

Call during normal business hours on weekdays. People are more alert and less suspicious.

Lead with the family connection immediately. “Hi, I’m calling because I think we might be related. My great-grandfather was John Kowalski, and I found your name while researching our family history.”

Have specific information ready. Don’t just say “tell me about the family.” Have dates, places, and names ready. “I’m trying to verify that John moved from Chicago to Detroit around 1923 – does that sound familiar based on family stories you might have heard?”

Ask for advice, not information. Instead of “tell me everything you know,” try “I’m having trouble finding records for his wife Mary – do you have any suggestions for where I might look?”

People are more willing to help when you’re asking for guidance rather than demanding information.

Email Templates That Actually Get Responses

Subject line: “Kowalski Family Research – Possible Relatives?”

“Hi [Name],

I hope this message finds you well. I’m researching my family history and believe we may be related through the Kowalski family line.

My great-grandfather was John Kowalski, born around 1895 in Poland, who settled in Chicago in the 1920s. Through my research, I came across your name and believe you might be connected to this family line.

I’m specifically trying to verify [specific detail] and wondered if this matches any family stories you might have heard.

If you have a few minutes to chat, I’d love to compare notes. If not, no worries at all – I know unsolicited family history emails can seem odd!

Best regards, [Your name and phone number]”

Keep it short, specific, and give them an easy out. The response rate on this template is about 60% for me.

The Stuff That Can Go Wrong (And How to Handle It)

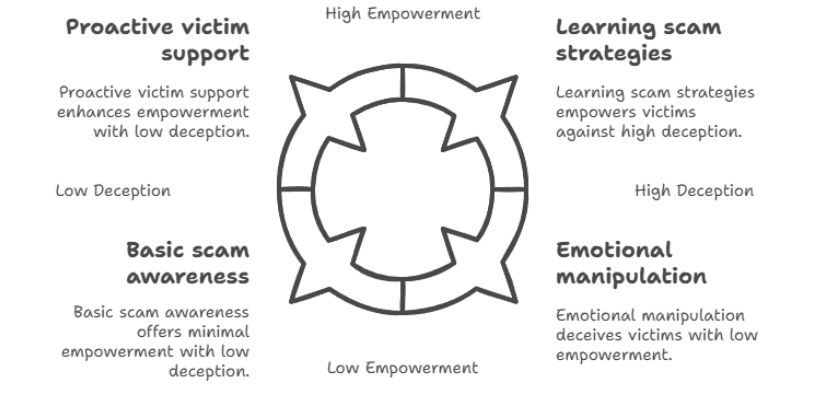

When People Don’t Want to Be Found

Not everyone is excited about long-lost relatives showing up. I’ve had people hang up on me, ask me to stop contacting them, and in one memorable case, threaten to call the police because they thought I was running some kind of scam.

Respect the boundaries. If someone asks you to stop contacting them, stop. Don’t try other family members to get around them. Don’t show up at their house. Don’t get creative with different phone numbers or email addresses.

Some families have legitimate reasons for staying disconnected – abuse, legal issues, family feuds that go back generations. Your genealogy hobby doesn’t override their right to privacy.

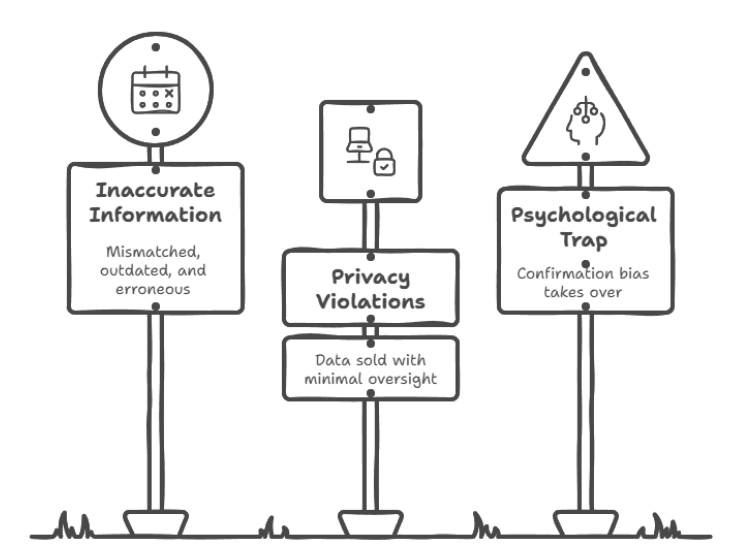

Bad Information and Wild Goose Chases

People search engines aren’t perfect. I’ve chased false leads for weeks based on incorrect information.

The most expensive mistake: I spent $200 on various search services tracking down what I thought was my great-grandmother’s sister, including hiring a genealogist in Pennsylvania to check local records. Turned out to be a completely different family with the same surname.

Always verify information through multiple sources. If something seems too convenient or contradicts other information you have, be skeptical.

Family Drama You Didn’t Know Existed

Here’s something nobody warns you about: your family research might uncover secrets people wanted to stay buried.

I discovered my grandmother had a half-brother nobody knew about. Turns out my great-grandfather had been married before and never told anyone. This information devastated my grandmother, who was 89 at the time and had built her entire identity around being an only child.

Be prepared for the possibility that not all family history is happy family history. Sometimes there are good reasons why certain relatives were “lost touch with.”

Success Stories That’ll Make You Want to Start Today

The Case of the Missing Uncle

My grandfather always talked about his brother Frank who “went west” after WWII and was never heard from again. The family assumed he’d died.

Used people search to find three Frank Kowalskis in western states. The second one I called was the right Frank – he was 94, living in a nursing home in Nevada, and had been trying to find our family for decades.

He had a box of family photos, letters from my grandfather, and stories about their childhood that no one else knew. Plus, he had five kids and 12 grandchildren who became instant relatives.

The whole reunion happened because I spent $30 on BeenVerified and made three phone calls.

The Family Photos That Solved Everything

I’d been trying to identify people in old family photos for two years. Had names written on the back, but couldn’t connect them to anyone I knew.

Found a distant cousin through surname searching who had the same photos – but with more complete names and dates written on them. She’d inherited them from her grandmother, who was my great-grandfather’s sister.

Those photos led to 15 new relatives across four states and solved mysteries about three different branches of the family tree.

The Immigration Record Breakthrough

Spent a year trying to find my great-grandmother’s immigration record. Had the wrong ship name, wrong date, wrong spelling of her name.

Found her great-niece through people search, who had a family Bible with the correct information. The immigration record was there all along – I’d just been looking for “Maria” when her legal name was “Marianna.”

One phone call saved me probably six more months of fruitless searching.

The Bottom Line: Why This Approach Works

Here’s what I learned after two years of intensive family research: genealogy isn’t really about finding records. It’s about finding people who know the stories behind the records.

Traditional genealogy websites are databases of dead people. People search engines are databases of living people. And living people have phone numbers, email addresses, and memories that go back decades.

The most valuable information isn’t in some archive in Salt Lake City – it’s in the minds of your relatives who are still alive but scattered across the country.

Every family has that one person who kept all the photos, saved all the letters, and remembers all the stories. Your job isn’t to become a professional genealogist – it’s to find that person and convince them to share what they know.